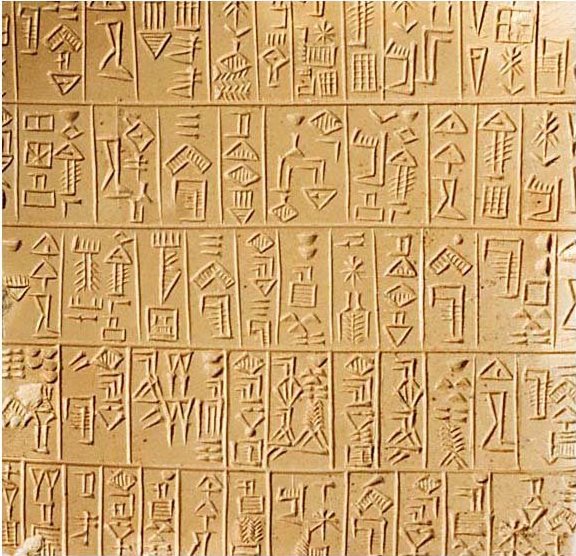

The Sumerian civilization, which thrived in ancient Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) between the 4th and 3rd millennia BCE, is known for its rich and complex cultural heritage. One of the most remarkable contributions of the Sumerians to world civilization is their written language, which is considered to be the oldest known form of writing in human history. The Sumerian text is a fascinating artifact of this ancient culture that has intrigued scholars and historians for centuries.

The Sumerians developed their writing system, known as cuneiform, around 3500 BCE, using a reed stylus to impress wedge-shaped marks onto clay tablets. They used cuneiform to record a wide range of information, including religious texts, legal documents, administrative records, and literary works. The Sumerian text is a testament to the sophistication and complexity of this early form of writing.

Religion, Mathematics, & Astronomy

The Sumerian text also includes a vast collection of hymns and prayers, which were recited by the Sumerian priests during religious ceremonies. These texts provide insight into the religious beliefs and practices of the Sumerians, who worshiped a pantheon of gods and goddesses. The hymns and prayers express a range of emotions, from praise and adoration to fear and supplication.

In addition to religious texts, the Sumerian text also includes a wealth of administrative and legal documents. These documents record transactions, such as the sale of property, the exchange of goods, and the granting of loans. They also include contracts and agreements, such as marriage contracts and business partnerships. These documents provide valuable insights into the social and economic structure of Sumerian society.

The Sumerian text is also notable for its contributions to mathematics and astronomy. Sumerian scribes developed a sophisticated system of numerical notation, based on the sexagesimal system (a system based on the number 60), which was used for mathematical calculations and astronomical observations. They also created an elaborate system of astronomical observations, which they used to track the movements of the planets and stars.

Anunnaki Mythology

The Anunnaki are a group of deities that feature prominently in the mythology of the ancient Sumerians. The word “Anunnaki” means “the ones who came from heaven to earth” in the Sumerian language, and they were believed to be powerful gods who ruled over different aspects of the natural world.

In Sumerian mythology, the Anunnaki were said to be the offspring of the sky god Anu and the earth goddess Ki. They were believed to reside in the underworld and the heavens, and were associated with a variety of natural phenomena, such as storms, earthquakes, and fertility.

One of the most famous stories involving the Anunnaki is the creation myth, which describes how they were responsible for creating human beings. According to this myth, the goddess Nammu used clay to create the first humans, and the Anunnaki were tasked with teaching them the skills and knowledge they needed to survive.

The Anunnaki are also associated with the invention of writing, as well as the development of agriculture and irrigation. They were often depicted in Sumerian art as human-like figures with wings, horns, and other distinctive features.

While the Anunnaki are primarily known through Sumerian mythology, their influence can also be seen in the mythology of other cultures in the ancient Near East, such as the Babylonians and the Assyrians. Today, they continue to be a subject of fascination for many people interested in ancient history and mythology.

The Sumerian text is a remarkable artifact of human civilization, providing a window into the beliefs, practices, and achievements of one of the earliest known cultures. It is a testament to the enduring power of writing as a means of preserving and transmitting knowledge across generations. As we continue to explore and interpret the Sumerian text, we gain a deeper appreciation for the richness and diversity of human culture and the remarkable achievements of our ancestors.